Nate Davis took an unconventional path to San Diego, California, but still embraces what it took to get there as he approaches his 14th season of being a professional quarterback.

With symptoms at which some doctors recommend patients head to the emergency room, Nate Davis played in the most important game in Ball State football history.

“You know my temperature was 104 that day. I should have never played.”

Davis speaks matter-of-factly, dropping this bombshell with the casual nature of someone who noticed the price of tomatoes had gone up the local grocer.

“Not messing,” Davis continues, with a light chuckle in his voice. “I woke up the day before the game and I was feeling a little sluggish. And then the day of the game it was… it was bad.”

The timing could not have been worse for Davis to feel under the weather: the day in question was Dec. 5, 2008.

Davis, the Heisman candidate quarterback of undefeated and Associated Press No. 12-ranked Ball State Cardinals, woke up in his hotel room in Detroit, with the MAC Championship Game hours away, and could barely function.

Three years of work culminated at Ford Field, and in the end, the harvest bore sour fruit. The three-score loss against Buffalo, in which he was responsible for several turnovers, was functionally the end of Davis’ Ball State career, one which saw him bring his alma mater to the national spotlight and the precipice of program glory.

Despite the nature of the loss, Davis tries to keep on the positive side more than a decade later. “[Thinking about the result] was more of a memory thing, saying that, you know, I did this with a bunch of guys that love the same thing that I love to do: to play football,” Davis says.

Another brief pause.

“…. Yeah, we fell short. But you know, all we could do is just learn from it and to move on.”

Photo by Gregory Shamus/Getty Images

It would have been easy to ruminate and develop a bitterness about how that cold December day could have gone, and no one would have blamed him. Human nature has a hard time with embracing failures.

But talk to him even just a little bit, and it’s clear Nate Davis is at peace.

Two mentors

Ohio is a football-crazed state. More than 40,000 varsity players at 700-plus high schools each year vie for the attention of college recruiters in the hope of parlaying a sport they love into a free education.

Davis loved football so much he eschewed cartoons— not exactly an easy choice to make at such a young, impressionable age— and took in all the football he possibly could in an effort to learn more about the sport. That he loved football so much is no real surprise; his older brother Jose played quarterback at Kent State from 1996-1999 and had an eight-year professional football career.

“My brother was my role model, so of course I wanted to do everything he did,” Davis said.

Davis would eventually make a name for himself at the helm of Bellaire High School’s football program, playing quarterback just like his brother.

Davis set the Bellaire football record book ablaze in his three seasons as a starter, setting high marks in passing yards (7,384) and touchdowns (81) while being named all-state and all-conference in all three seasons.

His performance was enough to draw a three-star rating from 247Sports in the recruiting class of 2006, garnering offers from all 12 MAC schools as well as Cincinnati and West Virginia. Ohio State also had reported interest.

Davis, however, had a stipulation: he wanted to play both basketball and football— just like his brother.

In the end, Ball State, Miami [OH], Western Kentucky and West Virginia were the schools that expressed interest in such an arrangement. The Cardinals ultimately convinced Davis to make the move to Muncie. Jose being a MAC alum was a major factor for Nate.

The move from Ohio to Indiana didn’t intimidate Davis, and neither did the jump in competition from high school to Div. I football.

“First day on campus, I really fit in well because we did a lot of passing drills — and that’s one of the best things that I can do is throw the football,” Davis said. “So once I saw that I can throw the ball and knew what was going on… that’s when I knew [and] I said, ‘OK, I can do this at this level for sure.’”

Davis, a true freshman, was immediately thrust into a position battle with incumbent fifth-year senior Joey Lynch, who had passed for 1,982 yards, 18 touchdowns and seven interceptions in the 2005 season.

The age difference and Lynch’s place as a returning starter could have made for a volatile situation. Instead, the situation elevated both Davis and Lynch to give each other their best in a competition that lasted from spring camp into the regular season.

Davis eventually won out three games into the 2006 season. He finished the campaign with 1,975 yards, 18 touchdowns and eight interceptions on a 61.8 percent completion rate, and had Lynch’s support in the process

Lynch’s response after such a spirited fight for the starting spot left an impression on Davis, who praised Lynch for helping him learn to be a better person through their shared struggles.

“[Lynch] showed me how to be a real teammate,” Davis said. “A lot of people could have been selfish in that, and [say], ‘No, I’m not going to help you or nothing like that.’ You know, Joey was a great teammate. That’s what he really showed me: how to be a great teammate and be a great guy in the locker room.”

Photo by Michael Allio/Icon Sportswire via Getty Images

The ascent

Ball State was an unremarkable Div. I program for the 31 years before Nate Davis arrived.

Exclusively winning four, five, six, seven or eight games every season from 1979 through 1997, Ball State would have embarked on the 21st century flying under the radar nationally. And it would have, if not for a disastrous two seasons, 1998 and 1999, that overlapped with the school’s most famous alum hosting one of the nation’s most popular TV shows at the time.

Ball State’s struggles over 1-10 and 0-11 finishes in ‘98 and ‘99 were, for better or worse, well-known across the country thanks to comedian and then-CBS Late Show host David Letterman (for whom BSU’s broadcasting school is named). These stretches were so devoid of anything to cheer on, Letterman — in a true poster’s fashion — turned his fandom of the team into a recurring bit.

Even before those rough seasons to close out the 20th century, the Cardinals had never won a bowl game at the time, and posted a winning record just 16 times in the program’s 33 years before 2008 at the top flight of college football.

In fact, the team had more seasons with four wins or fewer (nine) than seasons with seven-or-more wins (eight) prior to 2006— with four of those seven-plus win seasons all occurring from 1975-1978, the program’s first four years of Div. I play.

The seeds that sprouted Ball State’s historic 2008 were planted during the hard times when Letterman invoked the program for gallows humors, however. In 2002, the university hired then-Michigan defensive line coach and alum Brady Hoke to lead the Cardinals. Hoke, a starting linebacker on Ball State’s 1979 MAC Championship team, was tasked with reviving a BSU program which had largely floundered since his departure from Muncie as a player.

It was rough sledding initially for Hoke and crew. In his first three seasons, Ball State went 10-24 overall with a 9-15 conference record. 2006, Davis’ first year on campus, saw the Cardinals finish one game short of a bowl bid at 5-7, though, a promising sign.

More importantly, the Cards finished 5-3 in league play for the program’s first winning season in the MAC since 2001 (when the conference schedule was seven games as opposed to eight.)

2007 was Davis’ first season as a full-time starter, and he delivered positive results, throwing for 3,667 yards, 30 touchdowns and six interceptions on a 56.5 percent completion percentage while running for five more scores. His performance was enough to help the Cardinals go 7-5 in the regular season and qualify for the International Bowl in Canada to face Rutgers in the program’s first bowl game since 1996 (a loss in the Las Vegas Bowl to Nevada.)

The year-to-year progress was significant enough to make Ball State a dark horse in the MAC West division heading into 2008 season, with Central Michigan as the looming monster to slay.

Central Michigan was coming off of a MAC title, claimed with a 35-10 blowout of Miami in the conference championship. Head coach Brian Kelly was gone, taking the same job at Cincinnati, but the Chippewas returned MAC Offensive Player of the Year Dan LeFevour and had the promising Butch Jones taking over his first FBS head coaching job.

Ball State answered the call of dethroning CMU, and Nate Davis’ development was a major part of both the Cardinals’ knocking the Chips from atop the divisional perch and BSU’s ascent into the national rankings.

While his box score numbers were slightly down, Davis’ ability to make the big play when necessary fanned the flames for the Cardinals. He finished the 2008 campaign with 2,591 yards, 26 touchdowns and eight interceptions while maintaining a 64 percent completion rate.

When paired with running back Miquale Lewis’ 22 rushing touchdowns and one of the MAC’s best ball-hawking defenses (16 interceptions), the overall product produced a sterling 12-0 regular season.

In a moment perhaps most indicative of the turnaround, Ball State football came up on The Late Show not as a joke, but with Letterman campaigning for the Cardinals’ inclusion in the Bowl Championship Series. He even brought Hoke on as a special guest-presenter of the nightly “Top Ten” list.

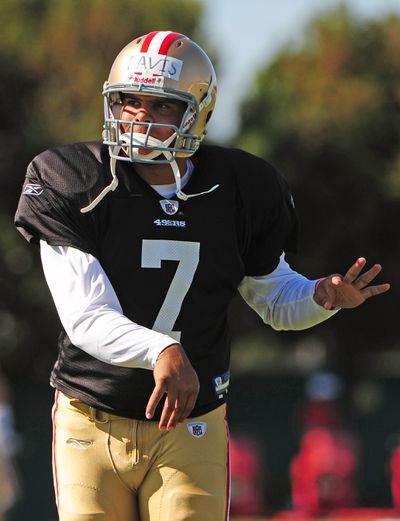

Set Number: X81153 TK1 R1 F121

Davis also started to draw individual attention the more the Cardinals won, landing on the Maxwell Award watchlist early in the season and being named a finalist for the 2008 Manning Award (won by Florida QB Tim Tebow.) Davis also finished eighth in the final voting for the Heisman Trophy (won by Oklahoma QB Sam Bradford.)

“[T]he reason why I had all that attention is because the other team guys that the other ten guys are on the field with me,” Davis opined when asked about what being voted for the Heisman meant for his personal legacy. “It’s not just a one man and one man thing, you know what I’m saying? That’s that’s how I play[ed] through it because I knew the guys around me was on the same page, so it wasn’t about no awards.”

The Heisman only applies to the regular season, something Davis was cognizant of in his answer.

“I didn’t care about no awards or nothing like that, because at the end of the day, you get judged on wins and losses and how many championships you won — ya know, how many bowl games you won. That’s what you get. You get noticed for… not how many accolades you get all this and that, you know I’m saying? I mean, am I very appreciative of it? 100 percent. But you know I’m more of the wins-and-losses guy.”

The 2008 season, however, did not end with the Cardinals’ 45-22 victory against Western Michigan at Scheumann Stadium.

There was still work to be done; a story to be told. And two weeks later, in Detroit, Nate Davis would find himself sick as a dog— with several different decisions on his mind.

Motor City Blues

When the Ball State team ran onto the Ford Field turf, so too did Nate Davis, dressed in full pads and helmet, ready to lead the Cardinals to a potential BCS bowl with a win in the MAC Championship Game.

He decided to play through his illness after meeting with the training staff and coach, taking the field as the starting quarterback, much like he had in the 12 prior contests.

Photo by: Gregory Shamus/Getty Images

Davis was not sharp to start the game, dropping a snap for a fumble late in the first quarter, which ultimately turned into a Drew Willy-to-Naaman Roosevelt passing score from two yards out to draw first blood.

Ball State steadied, responding with 10 unanswered points in the second quarter thanks to a Miquale Lewis rushing touchdown and a Ian McGarvey field goal.

The turning point proved to be with five minutes left in the third quarter.

On first-and-goal from the Buffalo nine-yard line, Davis snapped the ball and handed it off to Lewis on a shotgun read-option look, with Lewis speeding out to the left sideline on an angle to try and separate himself from oncoming defenders.

Lewis efforted to get the ball across the line, but the ball was ultimately spotted out of bounds at the one-yard line.

“We were up going into the third quarter and then there was a big call that our running back didn’t get into the endzone,” Davis recalled. “And after that play, it was kind of a downfall from there… I mean, straight landslide.”

Two plays after Lewis’ run, on second-and-goal from the eight-yard line after a false-start penalty, Davis took the snap and ran desperately towards the Buffalo sideline.

“That one play changed changed the whole game for us,” Davis said.

The play in question? Buffalo fans call it, simply, “The Fumble.”

Mike Newton etched himself in Bulls and MAC football lore forever by collecting the loose ball at the eight-yard line. He then ran untouched for a 96-yard touchdown, putting the Bulls up 28-17— a lead they never relinquished.

Buffalo won the MAC Championship Game by a final tally of 42-24, brutally ending Ball State’s undefeated run in dramatic fashion.

Photo by Gregory Shamus/Getty Images

Davis, even over a decade after the title game, still gets hung up on what could have been.

“If we scored [on the Lewis run], we go up by two touchdowns and we win the game… [W]e go, we run the ball, we think he gets in….” Davis sighs and brings up a crucial element of the story. “That’s why I wish there was, you know, the challenge flags, the replays all that back when I played.”

Instant replay was still brand-new in the NCAA in 2008. First adapted in 2004, each conference had different guidelines regarding how instant replay could be used.

At the time, the MAC had no allowances for coaches challenging calls on the field, with all reviews coming from the booth at official’s discretion.

Instead, things only got worse for Davis and the Cardinals. On the day, Ball State had five turnovers; all of which Davis was responsible for. “Those two plays right there stick with me for the rest of my life,” Davis reflected.

The last game of the season was played in Mobile, Alabama, as Ball State drew the Tulsa Golden Hurricane in the GMAC Bowl for a post-January game. The Cardinals had over a month to ruminate on the loss in Detroit, and looked every bit consumed by it in a wet, dispiriting 45-13 loss.

Processing the Draft

“I will come back.”

Those were the words that clamored out of Nate Davis’ lips after the MAC title game, just moments after a harrowing loss to Buffalo. “There’s no doubt about. It’s been the plan all along.”

This was despite having NFL scouts on site to watch him compete on the national spotlight. Despite all the attention he got throughout the season. Despite the awards he was listed for; the stats he posted.

Despite all that, Davis verbally committed to come back. And then, a month later, he was gone.

Davis opted to declare for the 2009 NFL Draft on Jan. 13, a week removed from the GMAC Bowl. The sudden change of mind was reported to be influenced in part by a return home to his native Ohio to talk his decision over with family.

“I know what I’m about to do won’t be easy,” Davis said in a press statement at the time. “But it’s what my heart and head want to do at this time. It’s the right thing for me and my family at this time.”

It was a decision which had been back-and-forth for some time. Newly-appointed head coach Stan Parrish, who was Ball State’s offensive coordinator and quarterbacks coach since 2005 under Brady Hoke, noted he had discussed the possibility with Davis for over a year.

“He’s like a son to me,” Parrish told the Associated Press at the time. “Like all fathers, you want your son to go out and do great in the world. I think he will.”

The decision left Ball State fans confused, with the circumstances surrounding the decision being a topic of discussion at the time.

“No, I do not,” Davis said when asked about if he had any regrets regarding the way he approached declaring for the draft, repeating for emphasis: “No, I do not.”

Davis was calculated in his explanation.

“It’s just when you lose nine starters… There’s only 11 guys on the field,” Davis said. “We have one guard…. We have one guard and one receiver [returning the next season] and I would have been the third guy. … It really weighed into it, you know? How big of a stock am I going to drop?”

“Yeah, maybe I could have made a difference [in 2009]. But not that big of a difference.”

Ball State went 2-10 the following season, without Davis at quarterback and with Parrish taking over head coaching duties after Hoke left for San Diego State the preceding offseason.

Regardless of his potential regrets or his reasoning, Davis was officially in the market for NFL teams, receiving an invitation to the 2009 NFL Scouting Combine. He was considered to be one of the top quarterbacks going into Indianapolis, with projections putting him in the high second round to mid-fourth round range.

Davis, in his recollection, met with all 32 teams, but had five organizations interested in him throughout the process.

“Tampa [Bay] was one. The [Indianapolis] Colts was another one, the [New Orleans] Saints. And then the [San Francisco] 49ers and then… the [New York] Jets.”

Curiously, his voice trailed off when mentioning the last one.

“[The Jets] were like a little iffy about me, you know? … They liked everything about me. It’s just they were just little iffy,” Davis said. “But I know why they just were iffy. You know, they never had a Black quarterback.”

[Editor’s note: JJ Jones Jr., an undrafted rookie free agent, broke the Jets’ color barrier at the position on Dec. 15, 1975, while free agent acquisition Quincy Carter started three games for the Jets in relief of Chad Pennington in 2004. We take the comment to mean a Black quarterback the Jets spent a draft pick on; Minnesota QB/DB Sandy Stephens was drafted fifth overall in the 1962 AFL draft by the then-NY Titans, but Stephens never officially joined the team after being told he would not be playing quarterback.

The Jets eventually drafted Geno Smith in the second round of the 2013 NFL Draft, making him the first Black QB in Jets draft history. Coincidentally, Smith later broke the New York Giants’ color barrier at quarterback in 2019, when he replaced Eli Manning late in the season.]

As for the rest of the teams involved in the draft process, Davis has a theory as to why he slid down the board: his dyslexia, a learning disability affecting the ability to read and process which he was diagnosed with in seventh grade.

“In football, I don’t have a learning disability,” Davis confidently told the San Jose Mercury-News after his getting drafted.

There were other concerns as well; Davis’ Combine performance was worse than expected, grading at a 1.06 Relative Athletic Score and having questions raised about his accuracy on deep passes (though many scouts were indeed impressed by his arm strength.)

Such concerns were enough to see a significant slide on the day of the draft, but Davis nonetheless kept the faith and followed the proceedings from his childhood home in Bellaire, Ohio.

“All through the draft process, they come out and told me: first-second round [for a draft grade],” Davis said, recalling the emotions on draft weekend. “So, you know, just waiting.”

The draft party continued to hold on to hope as well, with the Davis family all in attendance. Then, at pick #171 overall in the fifth round, a phone call patched through: it was San Francisco.

Davis beams as he talks about hearing the other voices on the line.

“Mike Singletary [49ers head coach at the time] called me…. He says, ‘would you like to be a 49er?’ And I was like, ‘You damn right I would!’ Davis said. “Once I got off the phone with him [and then-49ers GM Trent Baalke], I just stand in the circle and just hugged my family because, you know, it’s their dream come true.

“This is what every kid wants to do when they grow up and I have a chance to be one of the family to make it for us and you know, and I did.”

A tumultuous four-month period was finally over, and after all that work, Nate Davis packed his bags, said goodbye to Ohio, and headed out West.

“This is a business, man”

Davis still remembers his feelings and thought process on the day of his first NFL appearance in preseason action.

“I talked to my family, and they come and tell you: ‘Hey, just go out there and have fun. OK? Go out there. And have fun.’ And I was like, ‘OK, for sure.’ I went out there doing warm ups, you know…. The lights turn on. It’s like, ‘Oh man. You know I done made it’ …

“But in the back of your head, ‘I haven’t made it. You still gonna make the 53-man roster. There’s still a lot.’,” he added. “So of course, I just kept on doing it for my family. I just kept on out there and represented that last name on the back of my jersey for my family.”

The 2009 preseason saw Davis perform admirably, finishing 29-of-49 for 323 yards, two touchdowns and an interception over three games. He made the 53-man roster, sitting behind Shaun Hill and Alex Smith. He was brought back in 2010 to compete for the backup role.

Kyle Terada-USA TODAY Sports

Crucially, the 2010 NFL offseason saw the discontinuation of the “inactive third quarterback” rule, which allowed teams to activate a previously inactive quarterback to enter the game should both primary players at the position exit. (The rule was brought back in 2023 after the San Francisco 49ers were adversely affected by the restriction in the 2022 NFC Championship Game.)

Davis was held on the 49ers roster as an “inactive third quarterback” in the 2009 season, and with the new rule, it meant he would have to fight for one less spot.

Davis got some tough competition, as San Francisco traded away Shaun Hill to Detroit and signed former No. 1 overall pick David Carr in the offseason.

Davis had a decent performance in the Niners’ first preseason outing of 2010, going 5-of-6 for 84 yards in the fourth quarter against Indianapolis. His performance caught the eyes of media and coaches, and some even started to ask if he could have a chance at winning a role on the team.

“I feel like I don’t get rattled in games,” Davis said. “That’s the one thing I will say is I don’t think I get rattled in games. I think that, you know, the game always comes to me. It’s just that… I felt like the coaching got up a good game and I took what they gave me… I wasn’t trying to force nothing, you know, I was just playing, playing, playing. Taking what they gave me.”

The coaching staff gave him a chance in their next contest against Minnesota, sitting David Carr and allowing Davis to play the entire second half.

Davis finished 7-of-16 for 114 yards, with Singletary questioning some of Davis’ decisions in the contest, but the defining moment of his NFL career came with just under 10 minutes remaining in the third quarter and San Francisco looking at third-and-two at their own 11-yard line.

Davis faked the handoff to the running back, got to the end of his drop, then scrambled to the right to evade incoming pressure before getting into a throwing stance, with his back foot on the goal line, before unraveling a pass which floated in the air for 65 yards into the waiting arms of receiver Ted Ginn Jr.

The crowd roared and the team celebrated. It was an absolutely magical moment in a game which had otherwise been extremely ugly for both sides.

“Oh my goodness,” NBC’s Cris Collinsworth exclaimed. “This looked like John Elway throwing this ball… 50, 60… [6]5 yards. That was a shot.”

Davis and Carr continued to battle for the second quarterback spot in the remaining two weeks, with Davis going 11-of-22 for 103 yards, a touchdown and two interceptions in his last outing vs. San Diego— but Carr ultimately won the backup quarterback position, meaning Davis was put onto the 49ers practice squad. Davis wouldn’t see the field again, being released by the team at season’s end.

“This is the one thing that my brother always told me: ‘Hey, just remember this is a business, man. Always remember that, OK?’ And that’s what I learned about this NFL shit more than anything,” Davis said about the end of his Niners tenure. “This is more of a business than it is football. Because it comes down to numbers. …[I]t made me think, am I good enough to play in this in this league, you know? And that that’s just what I felt. Was I good enough? But of course, just by doing this all my life, of course I’m good enough. Like I got here, didn’t I? That was my mentality.”

Davis signed a futures deal with the Seattle Seahawks in 2011, but once again, bad timing forced him onto the street.

The NFL and NFL Players Association fell into a months-long collective bargaining dispute, meaning when Seattle cut him, no team was willing to sign him onto their roster.

Davis had to wait for some time, eventually joining the Indianapolis Colts for the 2011 preseason. He was cut unceremoniously after going 3-of-7 for 36 yards in his lone appearance, a loss to St. Louis.

Scott Rovak-USA TODAY Sports

This being 2011, there were really not many other places to go to play gridiron football for pay if you wanted to stay in America. A handful of spring leagues had lived and died in the 2000s; the XFL famously lasted one season, while the first iteration of the United Football League faced contraction issues at this time, eventually folding in 2012. Major League Football also never got off the ground despite significant investment in 2014.

Less than a year removed from his spotlight moment, Davis found himself a free agent without a home for the third time, going back home to try and come to terms with the direction his life was going.

“I just felt like, you know, I just gotta work harder,” Davis said. “I was down because, of course, you never want to get let go of your job and I just kind of told myself I need to work harder, work harder…”

Nate Davis had no choice: He would have to reinvent himself.

Entering the arena

When asked if he had a “welcome to the league” moment, Davis speaks up right away.

“Never had, never had that one,” Davis retorted. “You never have that in arena football. You don’t make enough money.”

Davis had to learn this lesson the hard way; he was cut just three games into the season by the Kansas City Command after completing 42-of-90 passes for 544 yards, nine touchdowns and five interceptions.

“We just felt like we had to do something,” Kansas City Command head coach Danton Barto said at the time in a press release. “We weren’t scoring points and in Arena Football you’re not going to win if you can’t consistently put the ball in the end zone. When something’s not working you’ve got to move on and improve your football team.”

For his troubles, Davis made approximately $3,000. Such princely sums made Davis one of the lucky ones; the league’s base salary in 2012 was reported at $830 per game for veterans and $775 per game for rookies, with an extra $250 starting bonus per game for quarterbacks.

The year prior, which had non-unionized labor, saw all base salaries at $341 after taxes.

It was a humbling moment; a crash course in the differences between different codes of gridiron football.

Davis was already familiar with how arena football worked; his brother Jose had played in the arena circuit for seven seasons, with six of those seasons at the peak of the AFL’s power, winning a championship with the Colorado Crush in 2005 as a backup quarterback.

But being on the field is a lot different from watching in the stands.

“[It] was definitely different,” Davis said about the transition. “The speed of the game, that was the biggest change, just learning the speed of the game. … The big adjustment is just how fast the game was because like I said, you do, you have a guy running full speed before he hits the line of scrimmage. … [I]t’d be some times where he get open so fast, I wasn’t ready. So that’s where it was big for me: just the speed of the game.”

A new opportunity to prove himself came about as a favor to an old teammate of his at Ball State.

Larry Bostic, who was a graduate senior running back for the Cardinals in Nate Davis’ true freshman year, called up Davis because his cousin, Julian Reese, was in dire straits.

Photo by Brian Bahr/Getty Images

Reese had been hired by the Amarillo Venom, a minor league arena team in the niche Lone Star Football League, on a permanent basis in 2012 after a four-game stint as an interim which saw his team go 3-1 to finish the season the prior season.

The problem was he inherited a roster without a quarterback, forcing Reese to consider coming out of retirement after two seasons away from the game.

“Once I got let go of Kansas City, [Bostic] called me and was like, ‘Hey man, I need a favor from you’,” Davis recalled. “And I was like, ‘what’s that?’ He says ‘hey, my coach, you know, Julian is down in Amarillo, Texas. He coaching down there. He need a quarterback here… You down?’”

Davis chuckles again, recalling the moment which would turn his career around. “And that’s where I went.”

Davis’ signing in 2012 proved to be instrumental for the Venom down the line, with Reese confident in his ability to get the former Heisman candidate back on the right path.

“(Davis) is a quarterback with pocket presence and natural talent,” Reese told the Amarillo Globe-Leader at the time of Davis’ signing. “This game will be easy for him. He is very humble to come down and play with us, and we’re going to get him going and hopefully get him back to where he wants to be.”

Reese could empathize with Davis’ situation. Reese, like Davis, was a former all-conference quarterback in college, playing his ball— like Davis— in Indiana for the Indiana State Sycamores. Reese also had a brief spell in the NFL (in 2002) before landing in the arena circuit, first appearing in the Texas-based Intense Football League.

Reese’s career was a successful one at the arena level, winning a championship in 2004 as part of the Amarillo Dusters— the precursor to the Venom— and would retire directly into a coaching job with the team after an eight-year run.

In fact, it was Julian Reese as a coach and person which stood out to Davis the most about his time in Amarillo.

“He was my mentor,” Davis said. “I give him a lot of credit; the reason why I’m so good. He’s the one that taught me arena football.”

Sean Steffen/AGN Media; image courtesy of Ball State Sports Link

Davis was an instant impact player who set multiple all-time franchise records, helping the Venom win back-to-back titles with the 2012 and 2013, with the performance of a lifetime in the latter game.

Davis won the title game MVP honors after a night where he led a 42-13 comeback run after the team fell behind 14-0 early in the game to Laredo, then had to re-claim the lead four different times— including on the game-winning 41-yard drive in the waning moments of the contest.

After the game, where Davis crushed the competition with three passing touchdowns and four passing touchdowns, he took to the microphone and declared to the crowd of 3,500 assembled at the Amarillo Civic Center: “You know who the real MVP was and that’s Amarillo.”

Despite the meager salary in the CIF (about $900 to $3,600 for a full 12-game season), Davis was happy with life in the Texas Panhandle.

“This whole time when I was in Amarillo, IFL teams hit me up… I just had a good thing going on in Amarillo. That’s the reason why I didn’t leave,” Davis said. “So I always been putting up good numbers, you know, say, when I was in the CIF I could. I turned down the CFL many times because I had good things going. I had a job [with a local auto repair shop], I trained kids, so I had everything going on in Amarillo.”

Davis would man the Venom’s move from the Lone Star Football League to Champions Indoor Football — a merger of the old LSFL and the Midwestern-based Champions Professional Indoor Football League — in 2015, qualifying for the playoffs every season and winning no less than eight games per season from 2016-2019, winning the Southern Division in 2016 and finishing either first or second in the regular season standings every year save 2015.

A renaissance in the West

Davis had multiple chances over the years to jump up levels of arena play and even had opportunities to play football in the Canadian Football League while in Amarillo, with both the Edmonton Elks and Montreal Alouettes interested in his services, but declined every invitation.

“Everybody talks about a dollar sign… but for me, I have so much going on with my family and I’ve got stuff going on with kids and all that, so it’s a little hard to to do stuff like that… thinking about going to a whole different country,” Davis said. “Just to play some football.”

But Davis would have no choice in his next career move, as the COVID-19 pandemic effectively shut down arena football in his area in 2020— including the team which embraced his period of growth.

Stephanie and Toby Tucker, who had owned the team since Davis’ arrival, were forced to shut down the team in 2020 due to the pandemic, but were ultimately never able to revive the club.

The Venom were eventually put up for sale in 2022 after missing two seasons in a row.

“I loved [the team], Nate said about the team’s dissolution. “They treated me well. I met a lot of good people. I have a lot of great memories over there. It sucks. I mean it. It really did suck because I know the owners and [it] suck[s] for them… to give up the team, and that’s because I saw when they first started the team. It really sucked to see them go down like that.”

After a successful eight seasons in Amarillo, Davis would have to find a new home, as COVID wreaked havoc across the country.

The Duke City Gladiators, located in Albuquerque, New Mexico, called up Davis after the news of the Venom’s cancellation, giving Davis a chance to prove himself at the highest stage of the arena game in the Indoor Football League.

Davis acclimated quickly, finishing his first season as a Gladiator with 2,901 passing yards and 86 total touchdowns (79 passing, seven rushing), completing 64.1 percent of his passes to help lead the IFL’s highest-ranked offense in points and yards per game, earning IFL Offensive Player of the Year honors in 2021.

2022 was a more trying year; Davis wound up injured early in the season and missed the entire season.

It took Davis a full year to get back to playing shape, and by the time he was getting back into the swing of action, something shocking happened: he had been traded to another team barely a quarter-way into the season.

The San Diego Strike Force, new on the IFL scene in 2023, were looking for a more permanent answer at quarterback and opted to pick up Davis from Duke City for a package of young players, including two quarterbacks in Demry Croft and Aaron Aiken and a lineman in Jeremiah Caine.

There was no warning for Davis, who had made Albuquerque his home over the last three years— and led the league in touchdown passes and passing yards at the time of the deal.

“Strangest thing I’ve been a part of [in my career] is [2023], … I got traded to a team to the last place team in the league,” Davis said about the move. “You practice Wednesday morning… You have good practice and then at 11:30 at night, a different coach calls you and tells you, ‘hey man, you’ve been traded to my team.’ No warning or nothing. Blindsided.”

It was something Davis kept in mind when the teams met in San Diego on May 21, 2023. He went 14-of-20 for 208 yards, six touchdowns and no interceptions in a 57-44 victory over his old team to move his new team to 3-5 on the year— while both QBs the Gladiators dealt him for rode the bench.

David Frerker

In his 10-game tenure as the Strike Force QB in 2023, Davis led the league in average passing yards per game (212) and was second-best in the league in touchdown passes (48), guiding San Diego to a 4-6 record— an amount of wins which doubled their win total prior to his arrival and eclipsed their entire 2022 season.

Nate Davis, in retrospect

Nate Davis, at 37 years old, still has the fire in his belly necessary to play football at a high level— which makes talking about his legacy difficult.

Davis was certainly aware of the criticisms lobbied in his direction throughout his career. Whether it related to the way he left Ball State, or his ability to play at the NFL level or why he was cut from the Kansas City Command (which was something he did not go in-depth on in our discussion.)

“I mean, you want all people to say nothing but good of you, right? That’s what, of course, that’s what everybody wants. But by playing this game, I’ve learned everybody’s gonna have their own opinions,” Davis said when asked about his legacy as a player. “It’s kind of hard to have everybody say good things about you. You’re going to have those people that don’t like me… I mean, that’s just the way it’s going to be.”

His reticence to reminisce is something Davis is cognizant of; he admitted during his interview he has never gone back to watch any of his old games on film. Not one game over three years at Ball State, two years in the NFL and 12 in the arena game.

“[T]here’s so many memorable moments that I don’t sit back and think of more enough,” Davis says. “But I’m living life out of this now. …Once I’m done playing, I think then I’ll start… saying, you know, ‘when I was playing,’ ‘all the good days’ and you know, saying all [that.]”

Even if Davis doesn’t actively seek out such memories, there are still reminders here and there.

Ball State finally elected Davis, who left the Cardinals as the school’s all-time passing yards and completions leader, to their athletics Hall of Fame in 2021, something Davis never had on his radar.

“Man, I was shocked,” Davis said. “Yes, I was very shocked. Because… I didn’t think that, only being there for three years… I wouldn’t even get nominated or anything like that. It was just It was shocking to me. Crazy.”

Davis, who hadn’t been to Ball State’s campus since leaving back in 2009, returned for his induction ceremony.

“I-I have a plaque, with my face on it,” Davis stuttered in excitement. “Yes, that- that’s one of the craziest things ever is that for the rest of Ball State’s life, my face will be on there.”

Davis also expressed stunned disbelief at all the athletic facility changes— especially the indoor practice field. “[W]hen I first walked in… [they said] the first thing we need to show you is our indoor facility, I said ‘what!?’”

“When it rained, nah, yeah, we outside practice,” Davis continued. “There was no, ‘Aww, we’re gonna take the day off,’ no. Nothing like that. We were outside. Snow, rain did not matter. You had to be out there. Now they have a whole indoor facility. A whole field that’s indoors. It’s crazy. I could not believe it.”

Davis also had an opportunity to reconnect with some old friends after his midseason trade last year, with Brady Hoke fresh off his final campaign as San Diego State’s head coach and Jeff Hecklinski, a former WRs coach at Ball State whose wife was Davis’ communications professor, both residing in town.

How it started > Hot it’s going

Former Ball State HC Brady Hoke and QB Nate Davis reconnecting at the San Diego Strike Force Practice@BallStateFB @qbnate8@ifl @sdstrikeforce#NateDavis #BradyHoke #SanDiego #BombsAway pic.twitter.com/mu4fAIkjNr— San Diego Strike Force (@sdstrikeforce) March 13, 2024

“How crazy the world is,” Davis remarked. It was a reunion which almost didn’t happen.

“I almost didn’t want to come to San Diego because I have a whole family in Albuquerque.” Davis said. “[T]hat’s the only sad part about this football business is, you know, just getting up and leaving.”

Family was a major theme for Davis throughout our discussion; whether it was following in his brother’s footsteps, or leaning on his loved ones for his decision to go pro, or even staying in the States to stay closer to home.

“Throughout the whole process,” Davis continued, “They’ve always been supportive, but now the last three years is where I’ve had the most support because of my girlfriend and her family. They support me more than anything; they’re big football fans and they’re big on family-oriented things.”

He’s also family-oriented in other ways; part of his decision to stay in the arena leagues for so long was the intimacy arena football offers in terms of the fan experience— which often targets families.

“I love the game,” Davis said. “I love the way the game is played, the interactions with the fans, I just… I just love the whole atmosphere… The excitement and the joy. You know, to see all the kids and the fans come on the field after the game. That’s what gives me all the excitement to go out there and keep on playing and have fun doing it.”

Part of his hesitancy to leave Amarillo was also steeped in family; Davis did not want to unroot his family unless he had to, and he had to leave a number of kids he was coaching to play football as well in order to pursue his career in Albuquerque.

“The main thing that that … sucked [about leaving Amarillo] was leaving the kids,” Davis said. “That was the hard part, working with these kids, getting to be better and then ‘oh man, I gotta leave because of me’, you know, saying like I feel like that I’m leaving the kids.”

Once he got to New Mexico, he helped to establish a travel league football team for 10-11 year olds— a project he still contributes to during the IFL offseason.

“I will be a coach for sure,” Davis says about his future after football. “Definitely for little kids. That’s what I’m into now. I don’t know if I will coach arena football or not— that’s that’s still up in the air— do have a good eye for it? yes. But I like doing this… working with little kids, grow[ing] their talents.”

It’s evident as the interview closes Davis is content with where football has brought him to this point.

He found his purpose in Amarillo; settled down roots in Albuquerque; and has more chances to define his already strong arena football legacy in San Diego. Davis started on the right track to kick off the 2024 season on March 25, with the Strike Force taking home a 32-26 victory in a defensive battle over his old team Duke City on the road in his return to Albuquerque.

The Strike Force with Davis at the helm are in the hunt for a playoff spot in a stacked Western Division as well, sitting at a 6-4 overall record as of June 8, with six weeks to go in the regular season.

David Frerker

But at the end of the day, for a man whose competitive spirit still burns bright after over 13 years doing battle on the miniature gridiron, who doesn’t think yet of his life after football, who still has a lot he wants to prove before he finally hangs up the pads, there’s one thing he wants people to remember him for at the end of it all:

“That I was a good pocket passer.”

Nate Davis can be followed on Instagram at QBNate8, while the Strike Force can be followed at SDStrikeForce on Twitter and Instagram. All San Diego Strike Force games are aired live for free on YouTube.

Many thanks go out to the Lauren Washington and David Frerker of the San Diego Strike Force for access to and photographs of Nate Davis, respectively. Thanks also go out to Kyle Kensing for his assistance in editing and research for this piece. You can follow his freelance college sports work at various outlets and subscribe to his newsletter The Press Break on Substack.